England to Barbados

On May 2, 1635 a 22-year-old named George Norton boarded a ship in London bound for the Caribbean island of Barbados. The ship, called the Alexander, was under the command of Captain Burche Coldham 140-141. This was a turbulent time in England. William Laud, who became the Archbishop of Canterbury in 1633, had sent commissioners into nearly every parish to try to stop to a growing Puritanical movement. Meanwhile, King Charles I clashed repeatedly with Parliament. Without their consent he forced changes in the Scottish church, levied a ship tax in inland areas, and invoked a centuries-unenforced medieval law to fine men who owned valuable property for not serving him as knights Lambert Burns 110. The religious, political, and economic turmoil may have influenced George's decision to emigrate.

Barbados was claimed in 1625 in the name of King James I of England. In 1627 it was established as a colony. It "would become the cultural hearth, the model for the rest of the English West Indies - and South Carolina." Edgar 36 At first the settlers struggled to survive. After clearing the thick jungle their early crops of tobacco and cotton failed to pull in a decent profit. From almost the beginning the planters used forced labor such as indentured servants. Edgar 37 Then, in the 1640s, just a few years after George Norton had arrived, sugar cane from Brazil was introduced. Strong demand for this sugar and the rum and molasses produced as a byproduct transformed the economy within 20 years. Land prices skyrocketed. African slavery began replacing indentured servitude as the main source of labor. A few planters became extremely wealthy, and they dominated the colony Edgar 37.

George Norton's will, dated May 3, 1665, reflects his success in Barbados' sugarcane industry. To a Mrs. Thomas he gave 8,000 pounds of muscovite sugar (a natural, unrefined sugar made from sugarcane). To Phenix Tyler he gave 200 pounds of sugar. To one servant, Robert Hele, he gave 4,000 pounds of sugar, and to another servant, Ann Stewart, he gave 500 pounds. He left 5,000 pounds of muscovite sugar to "John Clarke, a poor fatherless child which I have for some time past maintained and kept upon my own charge... which I will shall be paid unto him when he attain to the age of twenty years if he shall so long live to demand the same." To his brother John Norton, a resident of Killingworth [now called Kenilworth] in Warwick County, he left 5 pounds of "currant English money". To his sister Mary Bayly, "now or late wife of Mr. Richard Bayly of Coleman Street within the City of London," he left another 5 English pounds. He left 30 English pounds to his sister Hannah Walker, wife of Edward Walker. His remaining estate on the Island he divided between his three children, Mary, Hannah, and John. He doesn't mention his wife, so she may have already passed away by the time he wrote his will. Will of George Norton Full Text

Between 1640-1660 Barbados was attracting over two thirds of the total number of English emigrants to the Americas. By 1650 there were 44,000 settlers in the West Indies. Large plantations, high land prices and overcrowding began to force out the poor and to prevent others from establishing or expanding their own plantations. People began to look for a new place to settle Wiki 1.

Barbados to Charleston

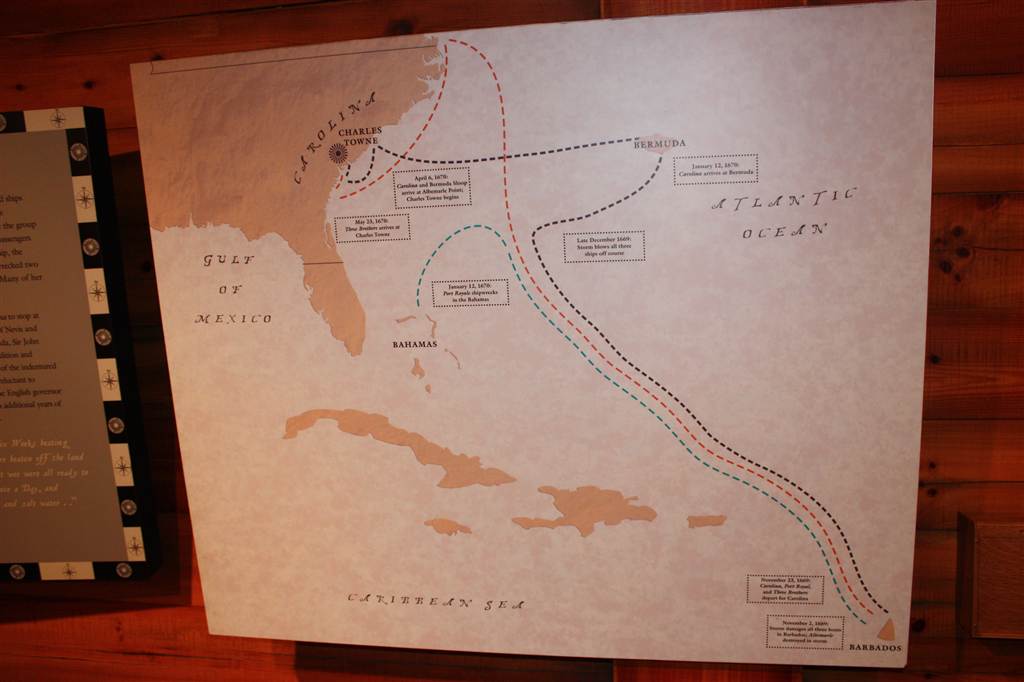

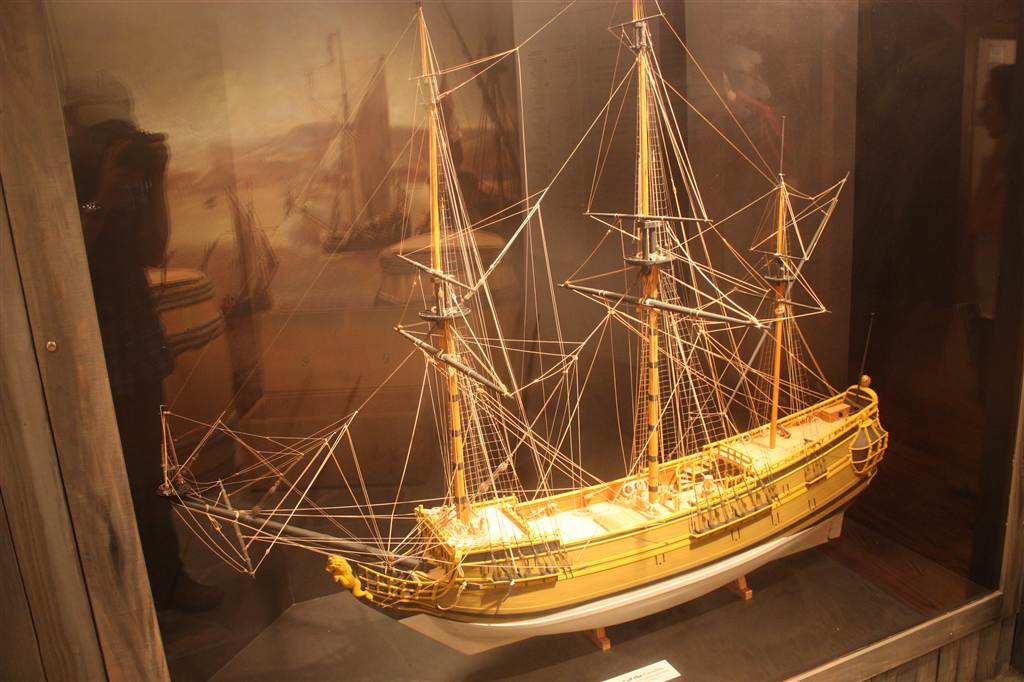

In 1663 King Charles II granted the province of Carolina between Virginia and Spanish Florida to eight English noblemen, the Lords Proprietors, as a reward for their efforts in helping him regain the throne Clement 11. A few years later, in mid-August of 1669, three ships under the command of Captain West, the Carolina, the Port Royal, and the Albemarle, set sail from England bound for this province. They stopped in Barbados along the way, and while they were there a tropical storm arose, wrecking the Albemarle. A new ship, the Three Brothers, was built in Barbados to replace the one that was lost.

In 1670 new passengers joined the fleet in Barbados and they continued on toward Carolina SC History 1. Among the passengers on the Carolina was John Norton, son of George Norton of Barbados Cheves 271 Lawton 53-54. High land prices and overcrowding in Barbados may have been among the factors that influenced John's decision to leave.

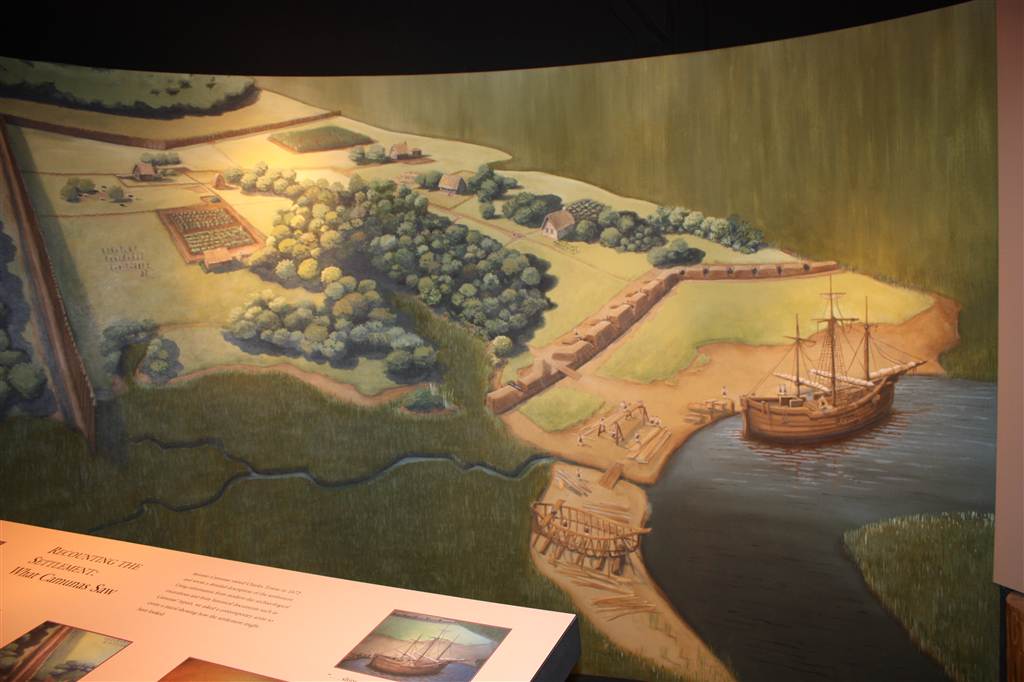

While sailing through the Caribbean, a storm caused the Port Royal to run aground. The remaining two ships headed on toward Bermuda. Still another storm drove the Three Brothers to Virginia. On 15 March, the Carolina was the only ship from the fleet to make landfall in Bull's Bay, thirty miles north of present-day Charleston Edgar 47. Dissatisfied with the first location, the colony moved in 1671 to the Western banks of Ashley River and laid the foundation of old Charlestown Ramsay 1. After he arrived, John planted in partnership with another "Carolina" passenger, Original Jackson, until 1673 Cheves 341. On August 20, 1681 he was granted lot #38 in "Charles Town" Smith 17.

Soon, other people whose descendants would become a part of the Norton family began to arrive, and in most cases they came from Barbados. In fact, between 1670 and 1690 54% of all white immigrants to South Carolina came from Barbados. In 1672 John Chaplin, born in England in 1636, came to Carolina via Barbados as an indentured servant of the Colleton family Rosengarten 61. Thomas Stanyarne, a Quaker, arrived with his wife Mary, their five children and four servants in May of 1675.

Jonathan Fitch and his wife Elizabeth, parents of John Norton's wife Sarah, arrived in 1678. Like Thomas Stanyarne, Fitch was a Quaker, a religious group known for the friendship and trust they had with the Indians. This quality was reflected in the fact that Fitch traded with the Indians, and that in 1680 he was appointed with five other men by the Lords Proprietors to negotiate disputes between Indians and Englishmen. He was also a planter. Lawton 55-56 On August 7, 1683, he was granted Charles Town lot #79 by the Lords Proprietors Langley 52-53 Smith 18. Jonathan Fitch died in 1691 and on October 28, 1691, John Norton sold the lot to Jonathan Amory.

On August 13, 1679, the barq Plantation, commanded by Aser Sharpe, sailed for Carolina from Barbados. Among the passengers were John Ladson and his wife Mary. The 1679 Barbados census showed that Ladson, a Quaker merchant, owned at least two slaves while he resided in St. Michael's, Barbados. He received a grant of land from the Lords Proprietors on September 14, 1682 and became a member of the Carolina Assembly in 1683. On May 10, 1695 Ladson was granted Charles Town lot #90, followed soon by lot #70 on May 30 Smith 18,19. Mary Ann Chaplin, grand-daughter of John Chaplin and John Ladson, and great-grand-daughter of Thomas Stanyard, would marry John Norton's son, Jonathan Norton, in 1732.

The South Carolina Lowcountry

The Nortons moved to the Lowcountry island of St. Helena after the Lords Proprietors granted 960 acres to John Norton in 1701. 400 of those acres were on St. Helena Island, and the other 560 acres were on what would later be known as Warsaw Island, a small island on the northeastern tip of St. Helena Island Rowland 2-3 Kvach 14. The Lowcountry, a region along South Carolina's coast that included the sea islands, was similar to the rice growing region of West Africa LDHI. John's land grant coincided roughly with the rise of rice cultivation that had begun with the introduction of seed from Madagascar in about 1694 Ramsay 113-114. By the 1750s, rice and indigo would make the planters and merchants of the South Carolina Lowcountry the wealthiest men in the colonies. These crops required a huge labor force, creating a strong demand for slavery. By 1720 Africans had outnumbered Europeans for more than a decade PEP.

John and Sarah had had at least 6 children: Sarah, John, George, Dorothy, Elizabeth, and Jonathan. Jonathan, the youngest, was born on St. Helena on July 14, 1705. Tragically, John passed away in September, only three months later. In his will he left his wife Sarah 1/3 of all his real and personal estate, and requested that the other 2/3 be divided equally among his children Langley, 373-374. Thus young Jonathan inherited 192 acres of Island real estate.

On May 16, 1732 Jonathan married Mary Ann Chaplin, daughter of John and Phoebe Chaplin, fellow residents of St. Helena's Island Smith 140. Mary Ann was born on July 22, 1716 and baptized Dec. 24, 1734 by Reverend Lewis Jones of the Church of England. The same reverend officiated at Jonathan and Mary Ann's wedding Smith 47. The original St. Helena's parish church where the wedding likely took place was built in Beaufort in 1724 and remains in the same location today, having been last enlarged in 1842.

While the St. Helena's Parish Register shows that Jonathan wasn't christened until he was nearly 21, on May 4, 1726 Smith 140, the church seems to have been an important part of his later life. Illustrating this, on August 21, 1756 Jonathan transferred to three trustees two acres on St. Helena Island containing a "chapel & vestry room for the public worship of God according to the Church of England." Langley 132 These buildings, not quite completed at the time of the land transfer, were built of tabby, a concrete made from lime, sand and oyster shells. In a book about the families of Hilton Head Island by the Rev. Robert Peeples, Peeples writes that Jonathan and his son William helped build that church on St. Helena together. The church was burned in a forest fire in 1888, but the tabby walls remain Peeples 3. On an historical note, the Penn Center, one of the first schools for freed slaves, was built across the street from the church following the Civil War. It was in a cabin on the Penn Center campus that Martin Luther King Jr. drafted his "I Have a Dream" speech.

Jonathan was listed in various land registries as both a carpenter and a planter Langley 52-53, 373-374. Apparently he was very successful. A few months after his death on April 28, 1774, an inventory conducted on his estate totaled nearly 8,800 English pounds. The estate included 22 slaves worth over £6,000; sheep, hogs, horses, cattle and oxen worth £800; two "rowing canoes" worth £150; wearing apparel £40; "The Crop made and unmade" £700; and shoemaker's or tanner's tools and tanned and untanned leather worth £417. The tanner's tools and leather may have come via Mary Ann's great-grandfather, Thomas Stanyarne, who was a tanner Lawton 59.

Jonathan and Mary had 10 children including William, born on October 22, 1746. That same decade also brought an important development to crop production in the Lowlands. In 1739 a young woman named Eliza Pinckney, eldest child of Lt. Colonel George Lucas, gained charge of her family's Wappoo Plantation near Charleston after her mother died and her father was transferred to a post in Antigua to become the island's lieutenant governer. Eliza began to experiment with cultivating and improving strains of indigo, which was in demand as a source of dye for an expanding textile market. By 1744 she was so successful that she used that year's crop to make seed and share it with other planters. The volume of indigo dye increased from 5,000 pounds in 1745 to 130,000 pounds by 1748 and nearly a million pounds in the late 1750s. The amount of money brought to the colony was second only to that brought in by rice cultivation, and planters like the Nortons grew even more wealthy Wiki.

William Norton grew up, as had his parents before him, on the Island of St. Helena Smith 141. He married Mary Godfrey of John's Island on Nov. 19, 1771 and together they had 7 sons and 3 daughters McCall 134.

One of William's best friends during this time was an Irish immigrant to America named George Mosse. Not much is known of George's life before he came to America. A practicing physician, his obituary states that he graduated from the University of Dublin. However, no records of his attendance can be found. He may have been related to another Dublin physician named Bartholomew Mosse, who in 1745 opened a maternity hospital called The Hospital for Poor Lying-in Women. If so, that would explain how George Mosse's family came to live in Ireland; Bartholomew was the sixth child of Reverend Thomas Mosse, who traveled to Ireland from England as a chaplain to King William III. While George Mosse was not one of Bartholomew's children he may have been a nephew.

Some time before 1767 George migrated to South Carolina and married Elizabeth Martin in the Parish of St. Thomas. Following Elizabeth's death during childbirth, George moved to St. Helena Island and married William Norton's sister, Dorothy Phoebe Norton. Together they had seven daughters. Mosse's extensive business dealings were described in an article by the Rev. Dr. Robert E. H. Peeples, the most prominant historian of the Lowcountry:

"... Dr. Mosse acquired a small acreage on St. Helena Island, continued his medical practice and opened a general store and established a profitable tannery and leather manufacturing business (all probably financed by inheritance from his deceased wife's estate). His 12-oared barge made monthly deliveries of his merchandise alternately in Charleston and Savannah, returning with needed supplies. Journeymen and apprentices augmented his small worforce of slaves. He planted benne from which sesame seeds were harvested for oil. He planted sugar cane from which he manufactured sugar and distilled rum. He planted grapes and made wines commercially." Peeples

Revolutionary War

The years following Mosse's arrival in South Carolina were turbulent ones. The French and Indian war in America, which ended in 1763, had been extremely expensive for Britain. In an effort to generate revenue London began imposing a series of tariffs and taxes upon the colonies. Colonists were outraged, arguing that because they had no representation in Parliament the taxes were in violation of ther rights as Englishmen. Over time the back-and-forth of resistence by the colonists and retaliation by Britain escalated until war erupted in 1775.

The Patriots won battles over the British at Moore's Creek Bridge and Charleston in 1776, so for a few years after this the British focused on the North. However, by 1779 the northern theater had become a stalemate. The British decided to shift their attention back to the South. In late 1778 the British captured Savannah and burned the Prince William (Sheldon) Parish Church in northern Beaufort County, South Carolina. Then in April of 1780 they began a seige of Charleston that gradually tightened, punctuated by periods of shelling. On May 11 a round of shelling caused several fires in the city, and finally the Patriot troops surrendered Scott.

The Continental Army began to reform at Charlotte, North Carolina under Horatio Gates, who had arrived in July. Many of the men had little experience in battle. Worse, more than half the just over 4,000 men were sick with disentery after eating green corn. Despite this, Gates ordered his men to march into South Carolina towards Camden, in which about 1,000 British soldiers were garrisoned. On August 16, 1780, Gates' troops were utterly defeated, suffering over 2,000 casualties Wiki. Dr. Mosse, who served as a militia surgeon during the battle, was captured by the British. He was marched to a prison in Charleston, and upon being paroled he returned to his family Peeples.

In May, 1781, Mosse was among over a hundred influential men in Charleston who were rounded up and forced onto the prison ships Torbay and Pack Horse. Held with Mosse on the Pack Horse was Charles Pinckney, Jr., who a few years later would take a leading role in the Constitional Convention. On May 18, 1781, Stephen Moore and John Barnwell, two of the prisoners, wrote a letter on behalf of all of them:

"We would just beg leave to observe, that should it fall to the lot of all, or of any of us, to be made victims, agreeably to the menaces therein contained, we have only to regret that our blood cannot be disposed of more to the advancement of the glorious cause to which we have adhered." Gibbes 75

The ships remained in the harbor for over a year before setting sail in August, 1782. Family legend, as recorded by Mosse's granddaughter, holds that as the prisoners were being shipped south toward St. Augustine they were allowed onto the deck because of the heat and overcrowded conditions below. As the ship passed Hilton Head Island Dr. Mosse dived overboard and swam ashore to freedom. While no other existing records support this particular story, in the years after the war a handful of other reports emerged regarding the escape of all prisoners on the ship. In these reports, the ship was actually heading north toward New York under the escort of a British frigate. No known first-hand accounts were left discussing what happened next. The scattered stories suggest the prisoners escaped from the hold and took over the ship, then headed to the coast of North Carolina. No one knows where they came ashore and the men didn't surface again until months later GeorgiaWriter.com.

William Norton had his own experience as a prisoner of the British, having been captured while serving as a lieutenant with the South Carolina Continental troops. William's granddaughter Martha Norton Buckner tells the story (edited later by his descendant Elizabeth Munsell Norton):

"His sister, Elizabeth Joyner, afterwards Graham (the 'Aunt Graham' of the narrative), hearing that he was sick, rode on horseback to the enemy's camp, with a permit she had obtained from their commander, asking for her brother. Having him placed on a horse, she returned, leading the horse right by their troops. She wore a cap with a white feather in it to show that she was on the American side. Every British officer pulled off his cap as she passed, and the ranks were opened for her to pass through. The Yankee army never did anything like that."

William's friendship with Dr. Mosse factored into a significant turning point in his life. Mosse, while initially an Episcopalian, made the decision to join the Baptist church. As there was no church in the area, he traveled to the mainland and was baptized a member of the Euhaw church by Rev. Joseph Cook, a prominant Baptist preacher. In 1789 Rev. Cook visited St. Helena Island. William had also been raised an Episcopalian and initially he felt so strongly about his own religion that he refused to listen to Rev. Cook. Eventually though, Mosse persuaded William to give the Baptist church more consideration. Finally William was convinced of the church's teachings of faith and immersion, and In 1790 Rev. Cook baptized William at Euhaw.

There was little support for the Baptist church on St. Helena Island and at times William was treated coldly by others. However, according to his paster, William T. Brantley, he had a calming influence on people. Over time he built a Baptist church on St. Helena Island, became a deacon, and gave sermons to the planters and the black residents alike, and membership grew.

Tragically, Mary Norton died in 1794. The next year William married a Mrs. Dixon, widow of Thomas Dixon and they had 4 more children. In 1816 she died as well. William passed away the next year, on March 7, 1817

Meanwhile, Dr. Mosse, feeling that his daughters would have better opportunities for an education in Savannah, moved his family there in 1793. They lived in "a large wooden house" owned by his sister-in-law Elizabeth Norton Graham (the same Elizabeth who had retrieved her brother William from the British during the Revolutionary War) at the corner of Broughton and West Broad Streets. Elizabeth was well off and had no children of her own Buckner. Martha Buckner described the living arrangement with "Aunt Graham":

"... she arranged with Grandfather and Grandmother Mosse that they should keep house and board her for the rent of it. She added her own furniture and house servants. So that was the family home the greater part of the time of their residence in Savannah. Aunt Jane Lawton and Aunt Mary Brisbane were married in it."

Mosse was a charter member of the Georgia Medical Society and organized the Savannah Medical College. In 1795 he was the founding Deacon of the First Baptist Church in Savannah. Rev. Peeples writes that "he complained that he 'made no dollars in Savannah' whereas he had 'made pounds (sterling) on St. Helena and Hilton Head.'" Peeples

In May 1806 Dr. George Mosse moved his family back to Black Swamp (Robertville), South Carolina where several of his daughters had settled. Elizabeth (Aunt) Graham built a house on the tract next to them Buckner. George died at Graham Hall there on February 17, 1808. His wife Dorothy died six weeks later. They were buried in the plantation cemetery, which is now lost Peeples. Elizabeth Graham lived many more years, passing away in 1832. She was the first person buried in the Robertville Churchyard cemetery.

Moving Inland

Rice cultivation in the lowlands, combined with a wet warm environment, created a perfect breeding ground for mosquitoes and parasites. Diseases were common McCandless 8. Plantation owners looking to escape these unhealthy conditions began to build homes on the mainland that they could travel to during the hottest parts of the year. William Norton was among them, purchasing land along the May River where the town of Bluffton now stands. He may have been motivated by something more than the climate. His granddaughter Martha Norton Buckner speculated that "after his much-loved brother-in-law, George Mosse and his sister Dorothy Phebe Mosse, moved to Sav'h, St. Helena lost its attractions for him." Buckner Bluffton's official website dates the first settlements to the early 19th century. However, the book "A History of Savannah and South Georgia", published in 1913, notes that Robert Godfrey Norton, son of William and Mary, was born at Bluffton in 1788 Harden 815.

Robert "went to Savannah while a youth, and entered the counting house of Jackson. He was baptized and joined the same church that Grandfather Mosse belonged to." Buckner

On June 2, 1808 Robert married his first cousin, Sarah Mosse, daughter of George and Dorothy (Norton) Mosse. The wedding was conducted by the Reverend Alexander Scott at Black Swamp, an area adjacent to Robertville, South Carolina Courier 3. Together, they had 7 children: Phebe (born about 1810), Alexander Robert (1812), Isabella (abt 1821), Martha (abt 1825, author of the family history referenced previously), Robert Godfrey, Margaret, and Adeline 1850 U.S. Census. Phebe was born in the Savannah home of Robert's aunt, Elizabeth Joyner Graham. They lost two of their daughters at infancy, and little Isabella died when she was only three, on October 15, 1824.

Robert followed the family occupation as a planter, working on land Sarah inherited from her father. The plantation was located on the Coosawhatchie Road, two miles from Robertville. He taught school in Robertville for three years Buckner. He also served as sheriff and ordinary (judge of probate) in the Beaufort district for a number of years. In addition to his home in Robertville he appears to have had a home on the old family plot on Lands End Road, St. Helena Island Rosengarten 529.

Robert and Sarah's son Alexander Robert Norton was born September 1, 1812 on a plantation on the May River Harden 816. Following in the footsteps of his grandfather George Mosse, Alexander became a physician. He graduated first from Charleston Medical College and later from Savannah Medical College, practiced medicine in Savannah and was the first official port physician of the city.

Alexander married Julia Elizabeth Greene in Screven County, Georgia on December 11, 1833 in a ceremony conducted by Rev. Joseph Lawton Buckner 11. Julia, the daughter of John Bryant Greene and Aurelia Selleck, was born on October 11, 1817 in Savannah. Her father, like her husband, was a doctor. He also owned a large plantation and the first pole boat to carry passengers and cargo between Savannah and ports up the river Harden 816.

Among Julia's ancestors through her mother were four passengers on the Mayflower: John and Joan (Hurst) Tilley, their daughter Elizabeth, and John Howland, who later married Elizabeth Tilley. John Howland is probably best remembered for having been blown overboard during a storm and somehow surviving. The story was included in a history of the Plymouth County written by fellow Mayflower passenger William Bradford.

"In sundry of these storms the winds were so fierce and the sea so high, as they could not bear a knot of sail, but were forced to hull for divers days together. And in one of them, as they thus lay at hull in a mighty storm, a lusty young man called John Howland, coming upon some occasion above the gratings was, with a seele of the ship, thrown into sea; but it pleased God that he caught hold of the topsail halyards which hung overboard and ran out at length. Yet he held his hold (though he was sundry fathoms under water) till he was hauled up by the same rope to the brim of the water, and then with a boat hook and other means got into the ship again and his life saved. And though he was something ill with it, yet he lived many years after and became a profitable member both in church and commonwealth." Bradford 59

Some time after Alexander and Julia's marriage they moved to Robertville, where Alexander continued his medical practice Harden 816. Together, Alexander and Julia had 8 children: Sarah Aurelia (1834), William (1837), John Greene (1838), Robert Godfrey (1841), Alexander Calhoun (abt 1843), Mary Eugenia (1845), Tallulah Susan (1849), and Joseph Stebbins (1851). Their daughter Sarah was only four years old when she died in September of 1839 and was buried in Robertville. Records show that in 1847 and 1848 Alexander was renting a pew in the Black Swamp Baptist Church in Robertville, the wealthiest Baptist church in Beaufort McCurry 110.

Alexander and Julia's son Robert Godfrey Norton married Martha Jane Edwards on June 13, 1861 Buckner. Martha, born on November 27, 1842, was a descendant of Revolutionary War soldiers. All of her great-grandfathers were in the war. On her father's side were William Edwards (d.1833) and John Pitts (1740 - 1781 or 1787). William Edwards enlisted in 1775 as a private in Captain J. Elliot's company, which was part of Col. Charles C. Pinckney's regiment. He then served from 1779-1781 in Capt. William Caldwell's company, 3rd South Carolina regiment. John Pitts commanded a company in 1780 in Col. Samuel Jarvis' 1st North Carolina regiment. On Martha's mother's side were William Cone (1745-24 June, 1816) and Robert Marlow (1740-1802). William Cone served as a private in McLean's regiment of the Georgia State troops. Robert Marlow served in 1781 as a private in the South Carolina militia DAR 278.

Martha's father was Rev. Joseph Chapman Edwards (4 Sep 1808 - 24 Jun 1892) from Effingham County, Georgia.

Robert graduated from Charleston Medical College and practiced medicine in Savannah for many years Knight V:2314. He also operated a plantation in Robertville. A former slave on the plantation, Ben Graham, was interviewed many years later in 1936 by a fellow church member in Savannah. During the interview he talked about his life as one of Robert's slaves. Overall he seemed to maintain a positive tone, but keep in mind that as he was speaking to a white woman it may not have been easy to say anything negative.

"It was a big plantation in Robertville and we was all happy. Dr. Norton made bosses of his slaves, he wouldn' hab white bosses, only colored ones. My father was a big boss and my uncle was a boss. Mr. Norton giv every one three acre of groun' a piece. He raise cow and hawg and 'taters and peas and he sell em to de owner." Blassingame 636

Civil War

Seething differences between the northern free states and southern slave states boiled over when Abraham Lincoln won the 1860 presidential election on a platform pledging to keep slavery out of the territories. Immediately seven states in the deep South, viewing Lincoln's pledge as a violation of their Constitutional rights, seceded and formed a new nation called the Confederate States of America. South carolina was the first to declare secession on December 24, 1860. It had the highest slave percentage of any U.S. state at 57% of it's population. 46% of its families owned at least one slave Wiki 2 Lincoln and most of the North refused to recognize the legitimacy of the secession.

On December 26, Major Robert Anderson of the U.S. Army moved his command from Fort Moultrie on Sullivan's Island to a more defensible position in Fort Sumter, a large fortress built on an island controlling the entrance to Charleston Harbor. When the merchant ship Star of the West attempted, at the request of President James Buchanan, to reinforce and supply Anderson, shore batteries fired on the ship and drove it away. This was the start of a long seige. On April 12, 1861, General P.G.T. Beauregard, in command of the Confederate forces around Charleston Harbor, opened fire on the Union garrison holding Fort Sumter. At 2:30pm on April 13 Anderson surrendered the fort and was evacuated the next day. Fortunately the battle resulted in no deaths on either side, but Lincoln called for 75,000 volunteers to suppress the rebellion. In turn, four additional southern states declared secession and a civil war began.

Records reflect Robert Godfrey Norton's part in the war. On March 4, 1862 he was appointed 1st Sergeant of Company I, 11th Battalion, Georgia Infantry Henderson. His Battalion was merged into the 47th regiment on May 12, 1862 Wiki 3, and that day he was made a Jr. 2nd Lieutenant in Company L. Then in October he was placed on General Harrison's staff. He was elected 2nd Lieutenant on February 18, 1863 Henderson Robert's obituary in the Savannah Morning News said that "he served 'with signal gallantry,' and was twice severely wounded. He subsequently was detailed an assistant surgeon and served in this capacity until the close of the war."

The war was as trying for the families left behind as it was for the soldiers. On 7th June, 1863, Robert Godfrey Norton Sr. wrote a letter from his home in Robertville to his granddaughter, Lieutenant Robert Godfrey Norton's sister. In the letter Robert Sr. expressed his resentment toward the North. He also wrote about his faith in God that gave him hope.

"God grant that we may be preserved from a murmuring spirit, and that the afflictive visitations of divine providence may be sanctified, and be productive of our spiritual advancement. The gloomy prospect now before us, of a devastating and prolonged cruel war, (a war unjustifiable and execrable on the part of our dastardly enemies) is under the control and guidance of Him who cannot err, and has promised that "all things shall work together for good to those who love Him, and put their trust in Him." I truly sympathize with you, my dear daughter, in the peculiar trying circumstances in which you are placed. I have no other consolation to offer, than that all power in the hands of a loving and sympathetic Saviour, who has promised "I will never leave thee nor forsake thee", and "Whom the Lord loveth he chasteneth". Let us unceasingly pray that God may hasten the time for calamities to be overpast; and that he will mercifully preserve and return unto us our dear Bobby, who is now at a remote distance from us, and under very arduous circumstances, but with commendable patriotism, engaged in repelling a merciless and rapacious foe, who are perservering, and with the most malicious intentions, seeking to divest us of every blessing we hold dear on earth. In due time, I am fully persuaded, God will visit them with that retribution which they deserve, and deliver an unoffending people from their diabolical power.- We have been unfaithful to our God, and need chastisement; but to our unprincipled foe, we have done nothing wrong. We deserve to be freed from their power and tyranny, and to have nothing to do with them in the future, but to pray that God would turn them from the error of their ways, or visit them with his retributive justice, and thwart them in their mad designs. It is undoubtedly our duty to pray for our enemies, in a proper sense, but not for the Devil or his emissaries except that God would thwart and restrain them in their vile purposes.-" Buckner Full Text

Later in the letter Norton wrote about recent events in the war, and expressed continued concern about his grandson, Robert.

"The abominable Yankees (perhaps you will have heard) are continually on the alert to make devastations on our coast as they are permitted to do.- During the past week, they burnt Bluffton, and many valuable residences, the week before, on the Combahee River, as well as the bridge at Combahee Ferry; and carried nearly 700 slaves from the plantations near the ferry.- We are continually expecting some raid from them, or attack upon the rail road between Charleston and Savannah.- Consequently, furloughs are not easily obtained, except for a very short period and in cases of emergency. I hope you will find it convenient frequently to write to some of us, and let us know what you hear from Robert, where he is and how situationed. Urge him to make God his friend, director, and preserver. Surely this is all-important with him. If it be practicable, it is desirable that he should write us frequently." Buckner Full Text

General William Sherman's capture of Atlanta, Georgia in September 2, 1864 was the beginning of the end of the Southern rebellion. From Atlanta, Sherman took 62,000 troops on a march through Georgia to Savannah with the goal of undermining Southern morale by making life so unpleasant for Georgia's civilians that they would demand an end to the war. They arrived in Savannah on December 21, 1864.

Ben Graham, Robert Godfrey Norton's former slave, was asked once if he had ever seen General Sherman. He answered yes, and related the following story:

"I was at Chicamauga too, and Dr. Norton had three horses which he kep' in different camps and currers (couriers) would take em back and forth and I look after em. I was 'rested in Washington County when I was ridin' one a Dr. Norton's horses, an one a Gen'l. Sherman's officer made me git off Dr. Norton horse and I rode his horse. I follow Genl. Sherman down his march to Savannah. I was wid his artillery and de men what had charge a de feed wagon look after me."

When asked what he thought when he saw General Sherman's Army burning everything in sight, he replied:

"I thought it was awful, but I couldn' do nutten. When we git to Savannah I tole em I belong to Mr. Charles Green (meaning Dr. Norton) and they let me go. [comment added by the interviewer]" Blassingame 635-636

Early in 1865 Sherman left Savannah and marched his army north toward Columbia, South Carolina. Because South Carolina was the first state to secede, he wanted to completely demoralize its people. Robertville stood directly in his path. The large extended Norton family was forced to leave. Mentioning the town, Lieutenant Colonel George Nichols, a Union staff officer, wrote an ominous entry in his diary:

"January 30th-The actual invasion of South Carolina has begun. The 17th Corps and that portion of the 15th which came around by way of Thunderbolt Beaufort moved out this morning, on parallel roads, in the direction of McPhersonville. The 17th Corps took the road nearest the Salkahatchie River. We expect General Corse, with the 4th Division of the 15th Corps, to join us at a point higher up. The 14th and 20th Corps will take the road to Robertville, nearer the Savannah River. Since General Howard started with the 17th we have heard the sound of many guns in his direction. To-day is the first really fine weather we have had since starting, and the roads have improved. It was wise not to cut them up during the rains, for we can now move along comfortably. The well-known sight of columns of black smoke meets our gaze again; this time houses are burning, and South Carolina has commenced to pay an installment, long overdue, on her debt to justice and humanity. With the help of God, we will have principal and interest before we leave her borders. There is a terrible gladness in the realization of so many hopes and wishes. This cowardly traitor state, secure from harm, as she thought, in her central position, with hellish haste dragged her Southern sisters into the caldron of secession. Little did she dream that the hated flag would again wave over her soil; but this bright morning a thousand Union banners are floating in the breeze , and the ground trembles beneath the tramp of thousands of brave Northmen, who know their mission, and will perform it to the end." McClary

They arrived at Robertville January 29, then marched to Lawtonville, leaving them both, plus a number of other towns in the Lowcountry, "virtually obliterated" Harrell 136. Robert Godfrey Norton, Sr's house on the Coosawhatchie Road near Robertville was burned Buckner. 150 years later in an article in the Jasper Sun Times, Bill Whitten, President of the Jasper County Historical Society, was quoted:

"So consequently Hardeeville, with the exception of the Methodist Church, and Robertville completely and a place called Lawtonville completely, those three places in particular in this area were all but obliterated. I mean they were just burned to the ground. Lawtonville never came back, a little town called Estill grew right next to it and Robertville now consists of a couple of buildings." Williams

As Sherman's army continued, about 1200 Confederates under Maj. Gen. Lafayette McLaws were posted at the crossing on the Salkehatchie River, about 40 miles north of Robertville. On February 2 Union soldiers began building bridges to bypass McLaws' troops. The next day two brigades under Maj. Gen. Francis P. Blair waded through the swamp and flanked the Confederates. McLaws was able to stall Sherman's advance for only a day before he was forced to withdraw toward Branchville. This would be one of the Confederacy's last stands against Sherman's sweep across the South. Both Robert and his brother Alexander Calhoun were part of that battle. Adding to the legacy of Nortons rescuing siblings from behind enemy lines (see William Norton and his sister Elizabeth) Robert's bravery was illustrated in a story Alexander told just before his death:

"About the 20th of February, 1865, there was a battle at Rivers Bridge at Saltcahatchi Swamp that lasted two days. The 47th Regiment was situated at the breastworks with the 3rd Georgia Regiment, and Wheeler's command was on their right. The lines broke about five o'clock. P.M. I, being on the left acting as a scout, was cut off by the Yankee lines. After our firing had fallen back about a mile and a half. My brother, Dr. Norton, found out through my Captain, Geo. C. Heyward, that I was in the Yankee lines. He mounted my horse and rode to the lines and brought me back. I did not recognize him on his approach. I drew my gun on him and called to him to halt, thinking he was a Yankee officer, but he knew my voice, and made himself known. He quickly took me up behind him and we rode out through the lines, and reported to the captain of the company, Geo. C. Heyward, and then we took up our march for North Carolina and reached Goldsboro about the last of March."

On April 9, 1865, Confederate Gen. Robert E. Lee surrendered to Union General Ulysses S. Grant. While a few battles and skirmishes took place after this, Lee's surrender is generally considered to be the end of the war. Robert Godfrey Norton was paroled (a pledge by a defeated soldier not to bear arms) on August 25, 1865 Henderson.

The war's end meant freedom for the slaves. Robert's slave Ben recalled his feelings at the time:

"I felt kin' a funny, cause I was loose. Dr. Norton say to me, 'Well, Ben', he say, 'you is free'. 'What you mean,' I say? He say, 'You is free as I am and you kin do anything you want to do'. I say, 'I don' know what to do'. He say, 'well, you come on down to Savannah wid me.'" Blassingame 637

Two years after the war, on July 13, 1867, Sarah, wife of Robert Godfrey Norton, Sr., died in a cabin on the land where their home had been burned by Sherman's army. Robert, by now elderly and disabled, moved into his grand-daughter's home with his single daughters, Margaret Norton and Martha Norton Buckner. He died there on May 26, 1868. Robert and Sarah were buried in the Robertville Churchyard Buckner.

Savannah

When General Sherman entered Savannah on Dec. 21, 1864 he spared it from the devastation his army later visited upon Robertville and so many other Southern towns. With their home in Robertville gone, and given strong family ties to Savannah, it made sense that by 1870 Dr. Robert Godfrey Norton and his family were listed in the Savannah census. By then Robert and his wife Martha already had three children, and they would eventually have two more. Their first child, Robert, was born during the war on January 18, 1864, a few months after Robert's regiment was sent to Jackson, Mississippi. The rest of their children were born in Savannah after the war's end: Francis Cone (29 Mar 1866), William Edwards (27 Dec 1869), George Mosse (29 Nov 1873), and Walter Abell (2 Oct 1881).

Robert resumed his medical practice, and was elected a member of the Medical Association of Georgia in 1875 SMN 3.

Robert and Martha's son George Mosse Norton graduated from the University of Georgia at Athens. He then studied medicine at Southern Medical College in Atlanta, graduating in 1898. His post-graduate study was at New York Post Graduate Medical School. He spent his career in Savannah, first in general practice, and later focusing more on major surgery. A biography written during his life remarked that in surgery "he has few rivals at this time." He was a member of the Georgia State Medical Society, the American Medical Association, and the Park View Sanatorium. He was also a Mason and a member of the Benevolent and Protective Order of Elks. He continued the family participation in the military as a member of the Georgia Hussars, in which he was a surgeon with the rank of lieutenant. The Georgia Hussars were a cavalry regiment founded before the Revolution and remained so until 1940 when they became part of the Georgia National Guard. From the Hussars, he received a medal for superior horsemanship in 1899 Knight 2314-2315.

On Oct 6, 1902, George married Leila Walton Exley in Savannah's Lutheran Church of the Ascension. Leila was born to Marquis Lafayette Exley and Emma Naomi Grovenstein Exley in Savannah on May 24, 1880. She came from a long line of Georgians, including her ancestor John Adam Treutlen (1734-1782), Georgia's first constitutional governor. George and Leila had five children together, all born in Savannah: Elizabeth Emma (28 Jul 1903 - 14 Feb 1997), Leila Lucille (20 Jul 1905 - 27 Oct 1999), Angela Willie (21 Dec 1906 - 10 Apr 2002), George Mosse (16 May 1912 - 6 Oct 2006), and William Nicolson (6 Aug 1915 - 4 Sep 1998).

For a number of years, until around 1920, George and his family lived in what was then described as one of the "most notable" of Savannah's historic mansions, located at 203 W. Oglethorpe Harden 668. The mansion is gone now, replaced by a hotel in the 1960s that has recently been turned into a residence hall for the Savannah College of Art and Design. A biography of George's life up to the point it was written in 1913 described the mansion in great detail:

"The city of Savannah is noted for its historic old mansions, and the home of Dr. Norton is one of the most notable. It was originally built by Joseph Waldburg as a home for his family, and after his death it was occupied for many years by his son-in-law, Colonel Clinch, a native of South Carolina. The house is an example of that substantial style of architecture used by men of wealth in a former age, when timber was plentiful, and veneer was unknown. The walls of the house are more than two feet thick, and the brick of which it is built is all rosined as are the hardwood floors. The ceilings, walls, partitions and other inside wood work are all of the costliest and most durable materials. The interior furnishings, decorations and the wonderful chandeliers were all imported from Europe and most of these still remain to add to the artistic beauty of the house itself. A delightful garden on the Barnard street side of the house is in keeping with the rest, and on the west side is another garden which affords a charming playground for the children. The property has one hundred and twenty feet of frontage on Oglethorpe avenue, and from a financial standpoint is one of the most valuable in the city. The house is built with two stories and a basement, containing many rooms of the generous proportions that our ancestors enjoyed. It cost $55,000 and required three years and a half in building." Harden 668

Hard Times

Over the last few years of George Mosse Norton's life a number of difficult events took their toll on him. Together, a rebuke by the Journal of the American Medical Association, the deaths of a number of close family members, an addiction to painkillers, and the loss of his mansion, may have all motivated his final tragic action in life.

In the March, 1913 edition of a monthly medical journal called "The Medical Summary", George published an article entitled "The Value of Starch-Treated Foods in the Dieto-Therapy of Dibetes Mellitus." The article first discussed diabetes in detail, including its history, definition and pathology, symptoms and complications, how to diagnose it, and the prognosis Mosse 14. Even during his time over 100 years ago a lot was known about the cause of diabetes and its effects on the body, but there were few effective treatments and death was inevitable within just a few years Mayo Clinic.

Dr. Norton's article eventually focuses on the problems diabetics have assimilating foods containing carbohydrates in the form of starch. Their bodies waste away and they starve to death because they can't process the starch. Finally, he offers a solution. While studying diabetes, someone had "coincidentally" brought to his attention "the virtues of a carbohydrate food which a diabetic could injest with impunity." It was a "new, starch-treated product known as the Jireh Diabetic Foods." He wrote that his patients who had returned after eating these foods for three months showed "remarkable improvement." The improvement, he related, had continued over a year. They hadn't been cured, of course, but they had a "new lease on life." The remainder of the article discusses the various Jireh Food Products, including Jireh flour, Jireh tea, Jireh biscuits, Jireh macaroni, and a number of other products Mosse 14. While the article seemed thorough in its examination of diabetes, it appears that its real purpose was to act as an advertisement for a specialty food.

The Journal of the American Medical Association took notice and quickly published a set of scathing responses. They called the Jireh products "dangerous and fraudulent," and numbered Dr. George Mosse Norton among the "humbugging physicians" that publish advertisements in medical journals in the form of medical studies JAMA 923 JAMA 1081-1082 .

"In our article on 'Flours and Foods for Diabetics,' two weeks ago, some space was given to a discussion of the Jireh Diabetic Food Company. This is a concern which sells a dangerous and fraudulent product for diabetics under the claim that the starch in it has been so 'treated' that it is not dangerous for those who suffer from diabetes. The Jireh concern has so juggled its advertising matter as to keep within the letter of the Food and Drugs Act while violating its spirit. We said in the article that the Jireh Diabetic Food Company was evidently intending to invade the medical journal advertising field. Our belief was further strengthened by the appearance of an advertisement - whether paid for or not, we do not know - in the form of an 'original article' that has already appeared in the March issues of the Southern Practitioner and the Medical Summary. How many other journals will print this 'article' remains to be seen. The article is entitled: 'The Value of Starch-Treated Foods in the the Dietotherapy of Diabetes Mellitus,' by one George M. Norton, M.D., Savannah, Ga... We had fondly hoped that the 'original article' method of advertising had gone out of date, thanks to the publicity this method of humbugging physicians had received from The Journal... The employment of methods belonging to an advertiseing era fortunately past will merely serve to emphasize the fact that the sale of Jireh Diabetic Foods depends on misrepresentation or deceit." JAMA 923 JAMA 1081-1082

Further blows came as within a period of just over ten years three of George's close family members died. First, his brother William, also a noted Savannah physician, died on March 28, 1911. Then in 1917 his mother passed away. Finally, on January 18, 1922, his brother Robert was shot to death RGN Death Certificate.

Already dealing with professional and family issues, somehow George injured himself. As a doctor he had easy access to strong painkillers, and while he took them to deal with the pain he became addicted.

George and his family eventually moved away from their large, beautiful mansion in Savannah. While the 1917 phone directory listed his residence as his mansion at 203 W. Oglethorpe, by the 1920 directory his residence was listed as "Isle of Hope," a marshy area adjacent to Savannah. His medical practice remained in Savannah itself. The 1919-1920 phone directory listed his office at 121 W. Jones Street, and the 1921-1923 phone books listed his office at 118 W. Jones Street.

Struggling with addiction and weighed down by the loss of his mother, two brothers, his home, and his professional reputation, George Mosse Norton shot himself on February 24, 1924 GMN Death Certificate. William, his youngest child, was only 8 years old. George was buried near his parents and brothers in the Bonaventure Cemetery in Savannah.

George's wife Leila and their children remained for a time at least on the Isle of Hope Savannah Phone Directory, 1924. In 1925 Leila rented an apartment at 713 Barnard St. in Savannah where she lived for several more years Savannah Phone Directories, 1925-1932 1930 Census. On October 17, 1966 she passed away and was buried next to her husband.